Roads

In pioneer days, the first “roads” were little more than dirt bridle paths or wagon trails that had evolved from Indian trails–which in turn had evolved from buffalo traces and deer trails. These roads alternated from dusty to muddy depending on the rainfall and could make travel very difficult.

Another factor that determined the paths roads took was the location of natural fords along creeks and rivers. These were shallow places with good footing where a river or stream could be crossed by wading, on horseback, or on a wagon. In upper Cleveland County in the area that is now Lawndale there was a ford in the First Broad River called “Gardner’s Ford.” A stage coach stop was located there on a route that ran from Lincolnton to Rutherfordton. Often inns and taverns operated near these stops. In the book, Our Heritage, there is mention of a tavern near the river where “weary travelers stopped for refreshment.” The tavern’s name was not given. It may have been the home of Richard T. Hord which stood just a mile south of the stagecoach route. A clue is found in the transcript pictured below.

After Cleveland County was formed in 1841, $125 was spent to build a bridge at Elliott’s Ford, an ancestor of the present-day US-74 West bridge across the First Broad River. (The ford had been named for Revolutionary war veteran Martin Elliott whose grave is on the hill on the north-west corner of the intersection of Hwy. 74 West and Polkville Road. His grave site was reportedly his rose garden at the time of his death in 1832.)

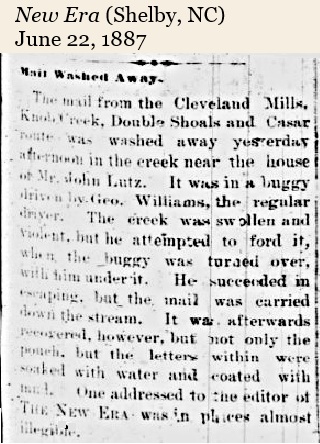

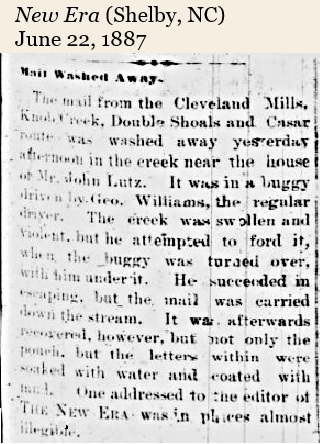

Sometimes even fords were unreliable and dangerous. In this case the mail carrier survived the swollen creek, but his mail did not.

At one time a ferry was operated on the Broad River in the southern section of the county. It was first known as Quinn’s Ferry, then later operated by Charles Ellis.

Ellis Ferry

Trade Route in the 1800s

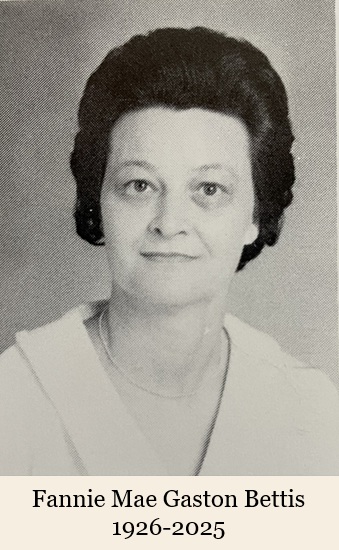

by Fannie Bettis

About the year 1800, an effort was made to establish a town on the main Broad River in the section of Cleveland county, which is now known as the Mt. Sinai community. The advantage of such a town would have been to afford an outlet for the agricultural products of this section.

The promoters of the project hoped to establish a large port for shipping the products of the farms of this section to markets at Charleston and Columbia, South Carolina. A port for receiving produce and shipping in the flat bottom scows and bateaux which floated up and down Broad river as late as 1840 would have meant a great deal commercially to this section.

This was strictly an agricultural community, and there was no market for the products because of inadequate transportation facilities. Since there was no way of disposing of surplus foreign products, the people had little money. Most of the trading was done by barter with Columbia and Charleston. The roads were poor, and it took months to get to Charleston and back.

River transportation was much quicker; therefore Charles and Rick Ellis, seeing the need for progress in travel and convenience, purchased 70 or 80 slaves and supervised the construction of a large wooden bridge across the Broad River to furnish a trade route between Gaffney, South Carolina and Shelby. Commerce began, and before long there was brisk business between the two towns. Things went smoothly for a time, but tragedy came–rain fell in torrents that year.

The Big Flood

Big Broad became a river twice its normal size, and the Ellis bridge which the slaves had built was washed asunder. It was about this time that President Abraham Lincoln issued his Emancipation Proclamation and freed the slaves. There was no labor to rebuild the bridge. A street in Gaffney, South Carolina today is named the Ellis Ferry road as a result of this trade route from Shelby to Gaffney.

A substitute for the bridge was failed a ferry boat. The ferry was operated by Charles Ellis, a son of Ben Ellis, therefore trade went on a black man named Adolphus Thompson operated the ferry and charged 25 cents for wagons, carriages, etc; 10 cents for a horseback rider and five cents for those choosing to walk. “Set me across,” people would yell to the black man on the other side of the river. Old persons in this community used to tell seeing great caravans of wagons at the ferry landing–some filled with apples, others with cabbages and produce. Largest crowds at the ferry could be seen on first Monday, which was trade day in Shelby.

At times travelers would be detained by the high waters and were compelled to camp at the ferry, sometimes for days. The camping grounds were near the traditional Indian campgrounds of Mt. Sinai, where even up to several years ago, arrow points an occasional tomahawk, and other relics were found. Many believed several Indians were buried on the south side of the river near the landing.

Flat Boats Remembered

Before his death, Sam Ellis of Shelby told of how the slaves polled the flat boats up the river from Columbia, hauling sugar, coffee and others scarce articles to the settlers. This area was called Burr Town at that time. He recalled how the boats unloaded in the cellar of Charles Ellis’s home and refilled with chickens, eggs, rabbits, and other wild game captured by the people living around the settlement.

Sam told of the laborious task of polling up the river and the ease of the return trip because of the water current. He remembered the tales of his father, such as the way molasses was hauled from Columbia to Burr Town. The Southern Colony built huge barrels and attached shafts to the ends. Mules were harnessed to the shafts, and a slave guided the animal. Thus the molasses was rolled to the river people.

During the civil war, Charles’s grandson (named unknown) hid the family’s mules beside the river where they escaped the eyes of northern troops. In the reconstruction days members of the Ku Klux Klan, who were being sought after by the carpetbaggers, found refuge there.

Years passed, and modern transportation developed; the little trading center declined and the dreams of Charles Ellis for a metropolis on the banks of Broad River were shattered. Years later, the sign “Burr Town” hung beside the home of Sam Ellis, (a great nephew of Charles Ellis). Bare fields now exist in the area of Ellis Ferry and Burr Town.

Source: Information gathered from Ellis Family History and by word of mouth from my mother, Mae Ellis Gaston, and my Uncle Sam Ellis.

According to the Encyclopedia of North Carolina, Canada experimented in plank roads as early as 1836. Thirteen years after, North Carolina experienced “plank road fever.” Plank roads were built of pine and oak sills, six to eight inches thick, placed on a well drained road bed, then covered crosswise with planks typically eight inches wide and three inches thick. The planks were subsequently covered with gravel or sand, which ultimately hardened into a fairly smooth surface. The drawback was that maintenance was constant and fairly expensive.

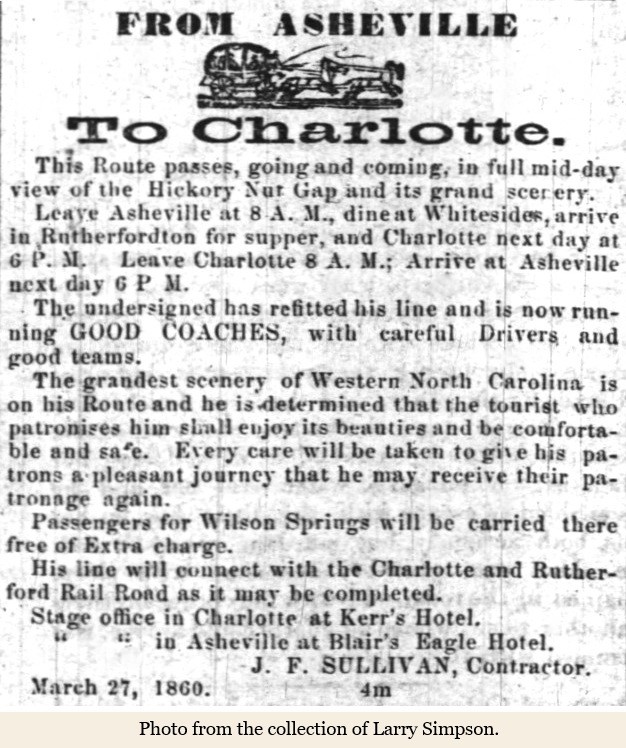

Between 1849 and 1871 in North Carolina, plank roads accounted for 84 chartered roadways, of which some 300 miles were constructed using state and private funds estimated upwards of $800,000. On December 27, 1852, an act to incorporate the Rutherford and Cleveland Plank Road company passed the state legislature. The road would run from Charlotte to Ashville. The initial stock was authorized for $200,000 to $300,000 if necessary. The act stipulated the road must pass through Rutherfordton and Shelby.

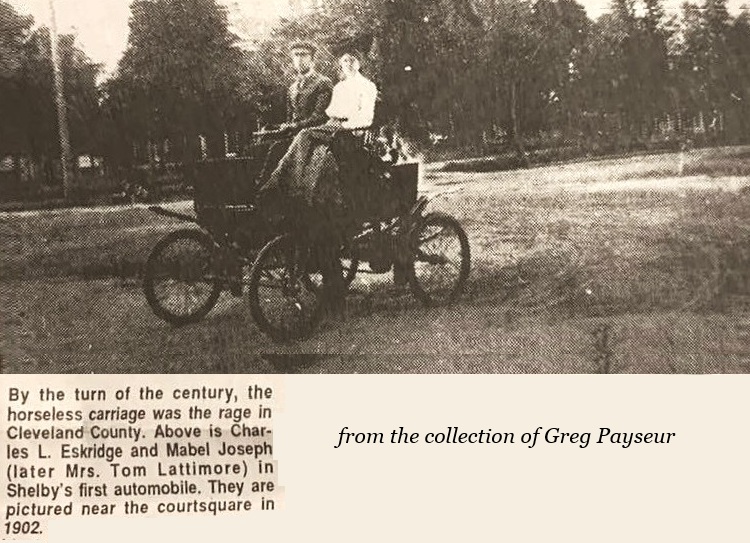

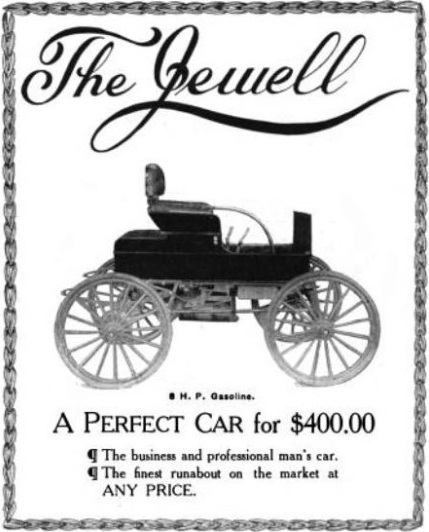

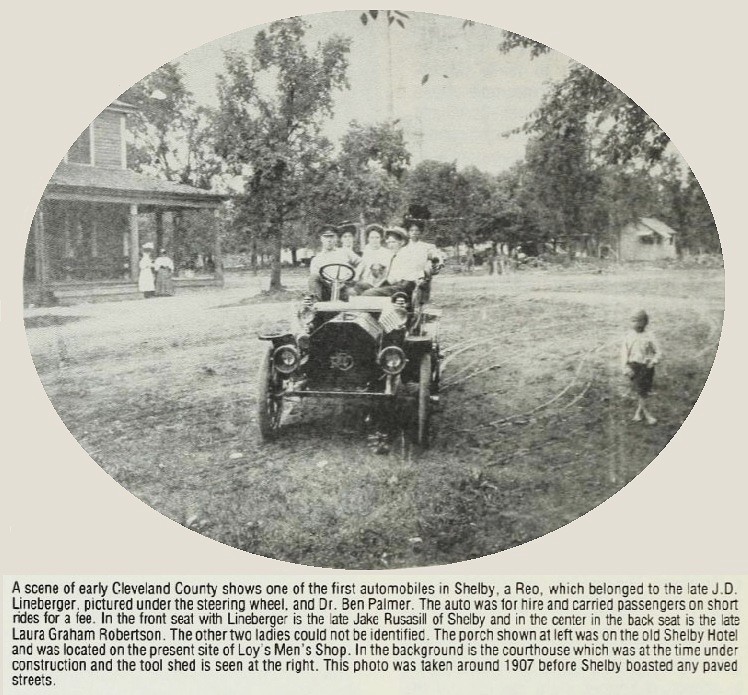

According to Our Heritage, the first person to buy a car in Cleveland County was Joe C. Smith of Shelby in 1902. He was followed by W. T. Carlton of Lattimore, who reportedly bought a Jewell.

When the first cars came on the scene in the early part of the 20th century, there were still no paved roads in Cleveland County. Road maintenance in the county was carried out much like jury duty. Able-bodied men between the ages of 21 and 50 were required by law to work on roads; most providing three to six days of work per year. Twice–in 1895 and again in 1903–the state legislature gave the county authorization to establish road taxes; Cleveland County citizens voted it down both times. Only voters in Number 2 Township approved the tax and subsequently hired Drury S. Lovelace at a salary of $1 per day worked.

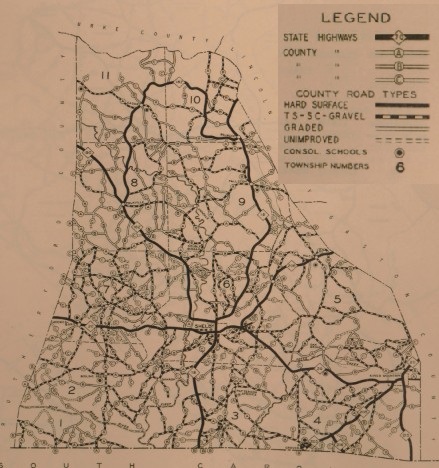

In 1909, the state legislature authorized the county to vote on the issuance of $300,000 in road bonds. The vote failed, but Number 6 Township (in which Shelby is a part) approved the issuance of their own $100,000 in road bonds. In 1911, Number 4 Township (in which Kings Mountain is a part) followed suit with the approval of $25,000 in road bonds. By 1919, every township in the county had sold road bonds and were building and maintaining their own road systems. Maintenance included the use of mules to drag timbers on dirt roads to make them smoother. “Paved roads” were initially just tar and gravel. The city of Shelby did not have streets paved with asphalt until the early 1930s, although sidewalks had been paved between 1907 and 1909.

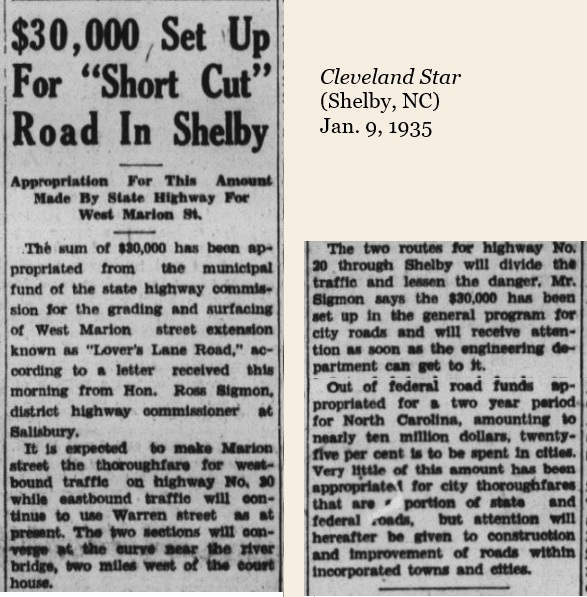

In 1921, the burden of road building and maintenance was lightened when the NC state legislature passed the “Good Roads” Act, shifting the responsibility for highway maintenance from counties and towns to the state government. Further financial help came the same year with the passage of the Federal Highway Act. Also known as the Phipps Act, it was a landmark piece of legislation that significantly shaped the development of the United States’ highway system. It established a national system of primary and secondary highways, allocated federal funding to states for road construction, and fostered cooperation between federal and state governments. NC Hwy. 18 was established in 1921 and became one of North Carolina’s original highways. Initially it ran between Shelby and Moravian Falls; later it was extended to the South Carolina line and north to NC 89 near the Virginia state line. Hwy. 20, running from the Gaston County line, through Kings Mountain to Shelby was the precursor to Bus. 74 through Shelby.

The image below shows a section of the road survey map in 1930. Notice the original road that is now Hwy. 74 Business (Marion Street in Shelby) was formerly Hwy. 20. Hwy. 150 to Cherryville was formerly Hwy. 206, and Hwy. 226 toward Polkville was Hwy. 182. The full, interactive map is here.

NC Hwy. 20 was renamed US Hwy. 74 about 1936. In 1958, the section between Kings Mountain and Shelby became a four-lane highway. It was renamed US 74 Business through Shelby in 1960 after the US Hwy. 74 bypass was completed. Interstate 85 opened in 1962 and a section of it has stimulated growth in the southeast corner of the county at Kings Mountain.

In the 1970s, planning began for a bypass around Kings Mountain. It was completed by 1983 and named for NC Senator John Ollie Harris of Kings Mountain. The Hwy. 74 bypass around Kings Mountain was constructed by interstate standards; the Hwy. 74 bypass around Shelby was not. So many businesses built along this section of highway that eventually a “bypass around the bypass” was needed. Shelby’s stoplights had become the only stops from Charlotte to Los Angeles, CA. Currently a US Hwy. 74 bypass north of Shelby remains under construction. This project began on the west side, near Mooresboro, in July of 2013. The section from there to the new Hwy. 226 interchange was completed in 2018. The section from the 226 interchange to the Hwy. 18 interchange to the Hwy. 150/180 interchange began in 2017 and opened to traffic on June 17, 2025. The final 4.1 mile segment from Hwy. 180 to Hwy. 74 on the east side began in 2023 and is projected to be completed by 2029 (although Congressman Tim Moore said in a statement on June 18, 2025 the segment “should open in a couple of years.”)

Railroads

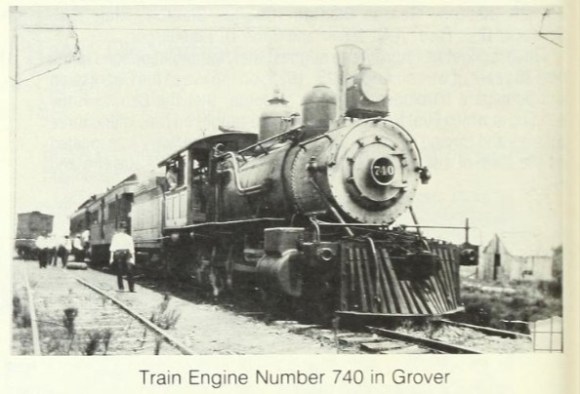

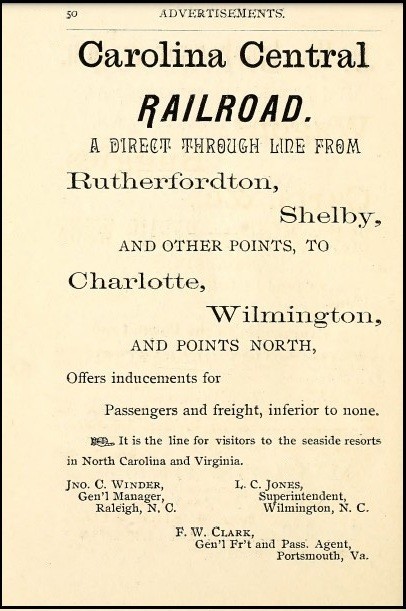

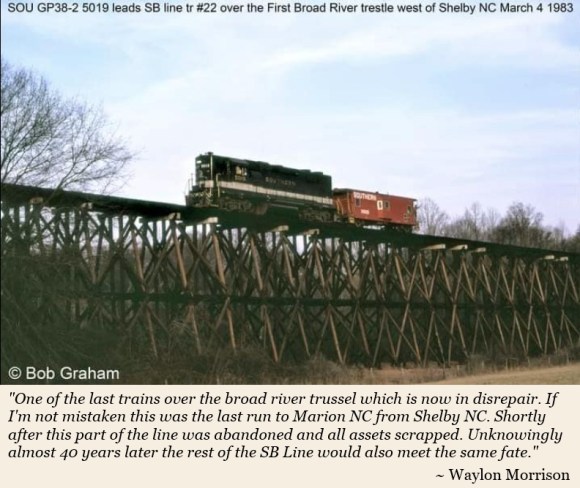

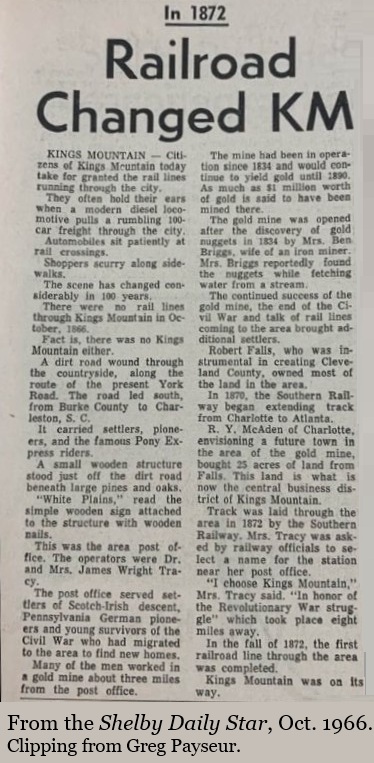

In 1872, Cleveland County received what would become a tremendous factor in the county’s economic development–the Atlanta & Charlotte Air Line reached Kings Mountain and Grover. Two years later, the Carolina Central Railroad completed its line into Shelby. Enhanced rail connections were largely responsible for a surge in cotton production during the 1870s, from 520 bales in 1870 to 6,126 bales by 1880.

Trains Through Grover, Earl, and Shelby.

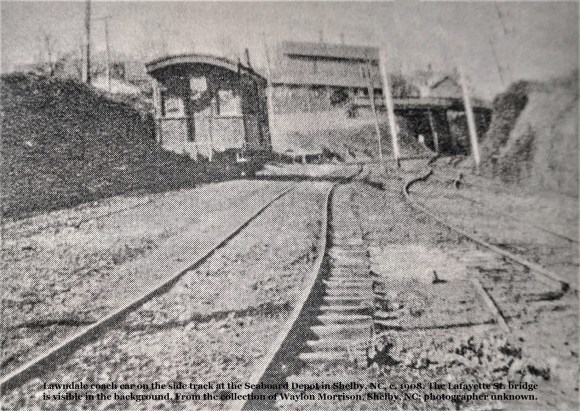

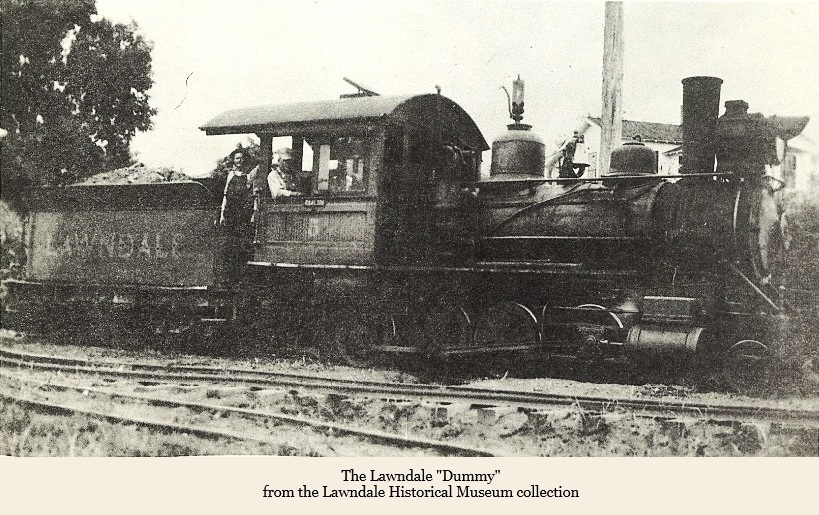

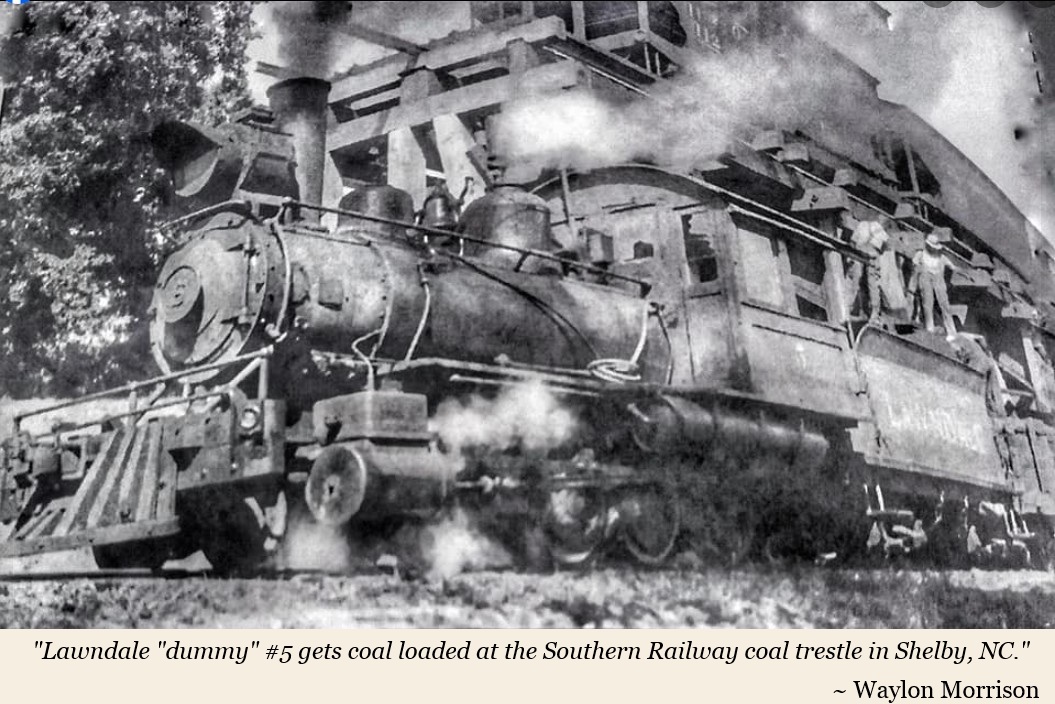

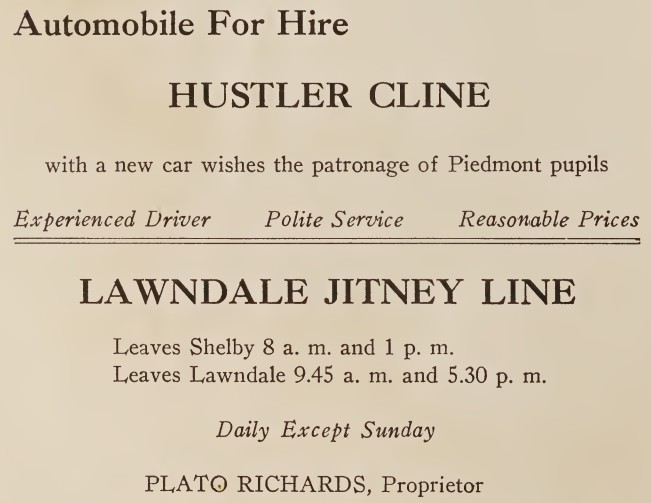

In the late 1800s Maj. Henry Schenck, owner of the Cleveland Mill and Power Company, grew frustrated with the condition of roads between Lawndale and the train depot in Shelby. They were hampering his ability to get his product shipped efficiently. He decided to build his own railway. He chose a narrow gauge train because they were being used less often by the large railway companies and he could get one cheaper. On November 11, 1899, the first regular train of the Lawndale Railway & Industrial Company ran on newly-laid tracks from Lawndale to Shelby. The train was referred to as the “Lawndale Dummy.” “Dummy lines” were found across the country and may have been named so because it was pulled by a steam locomotive that looked like a passenger train, only most of the cars that followed weren’t for people, but for cargo. Read more. . .

The Lawndale Dummy

In 2002, interviews were conducted by Thom Forney and others with people who had personal memories about the Lawndale Dummy. Those interviews have been posted to YouTube.

The old freight depot is in the center of the photo. The empty space in front of it was once occupied by the passenger station and water tower.

Public Transport

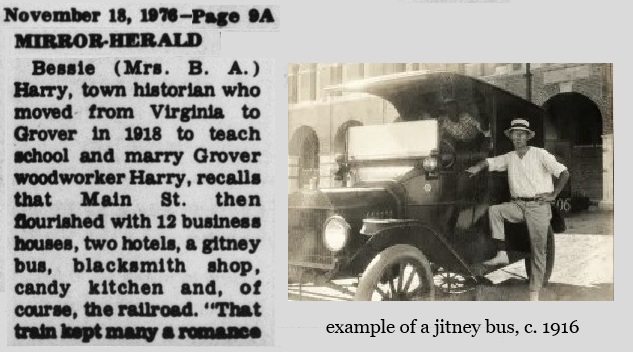

In Grover, a jitney bus operated to shuttle people around. The photo below is not the actual one in Grover, rather it is an example of a jitney bus. (The article misspells the word as “gitney.”)

The Transportation Administration of Cleveland County (TACC) was founded in April 1988. TACC is a non-profit agency providing on-call, scheduled ride solutions for rural and general public transportation in Cleveland County. TACC website.

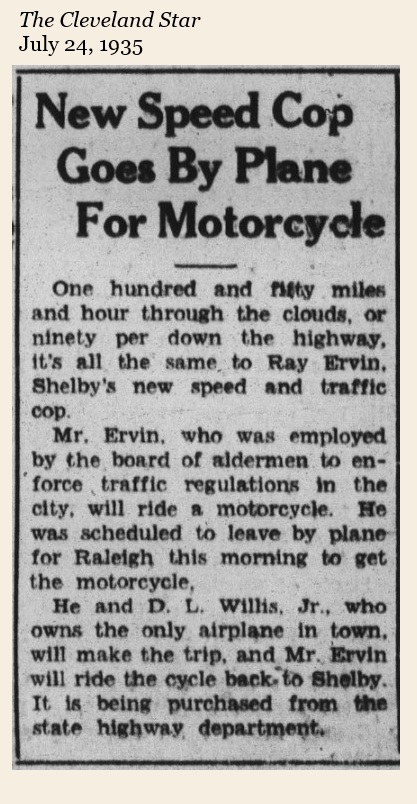

Airports

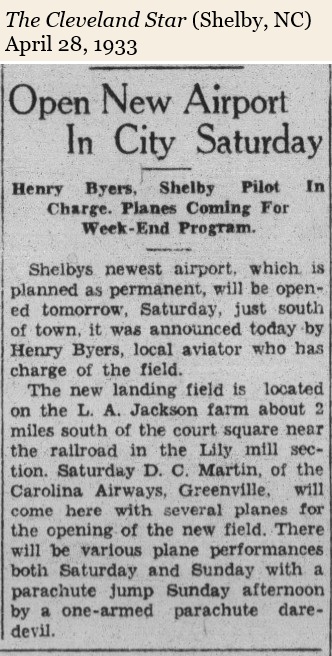

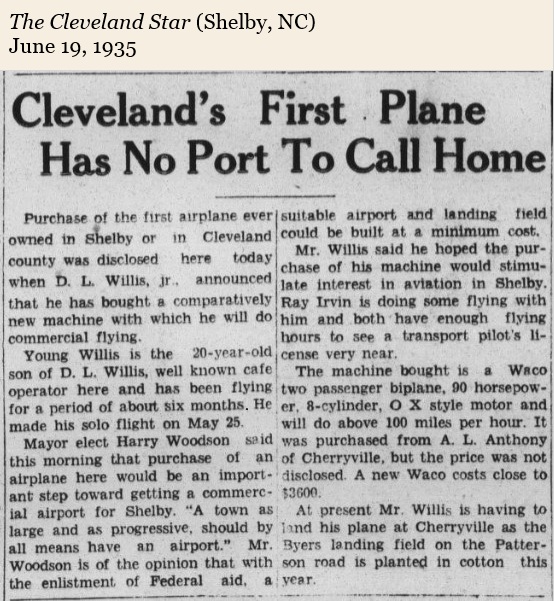

The first person in Cleveland County to own an airplane was David Lee Willis, Jr. Willis was just 20 years old when he bought a 1934 Waco model plane after receiving his pilot’s license in May of 1935. As part of a film promotion, Willis used Marion Street in Shelby as a runway, taking off from in front of the Rogers Theater and becoming airborne just after passing under the traffic light at the intersection of Marion and N. Washington Streets. He also helped out the police department on at least one occasion, as the clipping below shows.

Another airport opened in 1944 under the operation of Glee A. Bridges. It was just a few blocks from downtown Kings Mountain. Bridges Drive was once the runway for his airport.

Airport Road connects Hwy. 180 North to Fallston Road. It was named for a small airport owned by Paul Bridges that was once located on the northwest corner of 180 and Airport Road.

In Polkville, architect Fred Simmons had a short, dirt airstrip on his property located across from Union Baptist Church. In 1979, the strip was home to Carolina Sky Dive, a skydiving school run by Art Patterson of Shelby.

To the right is the former home of Fred Simmons.

The Shelby Municipal Airport located between Shelby and Boiling Springs opened in 1958. At some point its name was changed to the Shelby Regional Airport. In 2007, the city of Shelby took over the operation of the airport and the name was changed to Shelby–Cleveland County Regional Airport. In 2010, significant upgrades and improvements were made, including a new 5,000 sq ft terminal building. In 2019, the airport received a $225,000 grant to update its 20-year layout plan.

This facility is assigned EHO by the FAA but has no designation from the IATA. The airport’s ICAO location indicator is KEHO. For the 12-month period ending July 2, 2023, the airport had 18,200 aircraft operations, an average of 50 per day: 99% general aviation and 1% military. At that time there were 71 aircraft based at this airport: 65 single-engine, 4 multi-engine, 1 jet, and 1 helicopter. Info.

Postal Service

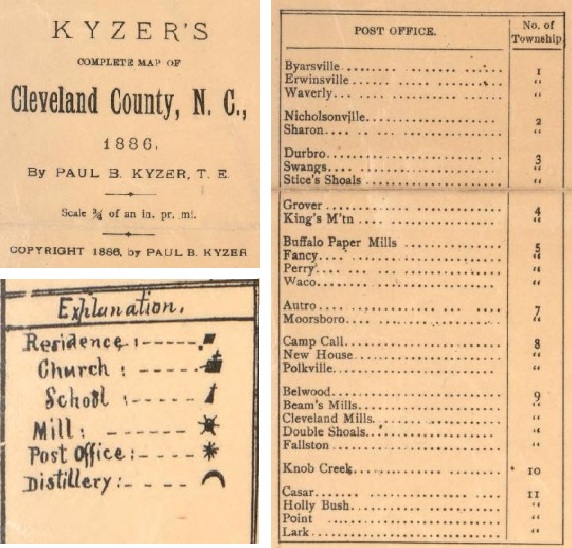

Before Cleveland County had good roads and rural mail delivery, the location of post offices often corresponded with the location of stage coach stops and train depots. Mail could be picked up at local stores as well, where the storekeeper was also postmaster.

In 1886, topographical engineer Paul Kyser drew a map of Cleveland County. His map indicated the location of homes, schools, churches and post office. He included the inset shown below on his map.

In contributing to the publication of Our Heritage (1976), Dr. Wyan Washburn conducted research into Cleveland County’s post offices and found others that were used in early days. The table below summarizes his findings.

| town/village | location |

| Byersville Erwinsville Waverly | Byers Family Cemetery at Ellis Ferry |

| Nicholsonville Sharon | at Settlemyre’s Ferry |

| Durbo Stice Shoals Swangs | near Pleasant Hill Church became Patterson Springs |

| Grover Kings Mountain | (was Whitaker) (was White Plains) |

| Buffalo Paper Mill Stubbs Fancy Waco | Buffalo Creek, Cherryville Rd end of Seaboard Railroad |

| Shelby | |

| Autro Mooresboro | near Rehobeth Church |

| Camp Call New House Polkville Ola Pearl Bead | Ola and Pearl were near Polkville. |

Beams Mills Cleveland Mills Double Shoals Fallston Love Joy | Beam’s Mills were originally on Buffalo Creek. When it switched from water power to electricity, it was closer to Pleasant Grove Church. Love Joy was toward Casar. |

| Knob Creek Paso Shade Zite | Knob Creek vicinity |

| Black Rock Casar Holly Bush Point Lark | Black Rock became Belwood. Holly Bush was at Jack Morrison’s Mill. Lark was in the Mt. Moriah area near Casar. |

| DePew | near Washburn siding on the Southern Railroad. |

| Delight | “in the Eaker settlement” |

| Beattyville | 3 mi. west of Shelby and north of Ora Mill near Brushy Creek |

| Crocker | SE of Shelby |

| Neals | near Oak Grove |

| Memory | Drury Dobbins community, just across the Rutherford line |

These dozens of small post office communities began to disappear after the establishment of the Rural Free Delivery program passed by the federal government in 1896. Made possible by better roads, Rural Free Delivery began in Cleveland County in 1902.

Into the 20th century, postal routes periodically changed or were renumbered. One resident, born in 1914, remembered having six different addresses although they lived at the same house from 1939 to 1990. This problem changed in 1989 when the NC General Assemby passed House Bill 510. This bill authorized the Cleveland County Board of Commissioners to delegate its authority to name roads and assign street numbers to the Cleveland County Planning Board. Over a period of time, all roads in the county had an official name and all homes had a standardized address.

In 1996, the North Carolina Postal History Society published a four-volume set of books titled, Post Offices and Postmasters of North Carolina. These carefully prepared books, under the editorial leadership of Vernon S. Stroupe, documented not only the post offices and postmasters of the 6,881 different post offices in North Carolina from the pre-revolutionary times to modern times, but also illustrated all known postmarks from these offices used before the twentieth century. Their history of Cleveland County postal service is summarized here. Digital NC has an 1912 map of rural mail delivery routes as well.

With the advent of the Internet and Optical Character Recognition (OCR), more recent research has revealed more details about the post offices of Cleveland County. J. D. Lewis has discovered early postmasters, dates of creation and closures, etc. He has summarized this research on his website carolana.com.

Cleveland County Post Offices

Telecommunications

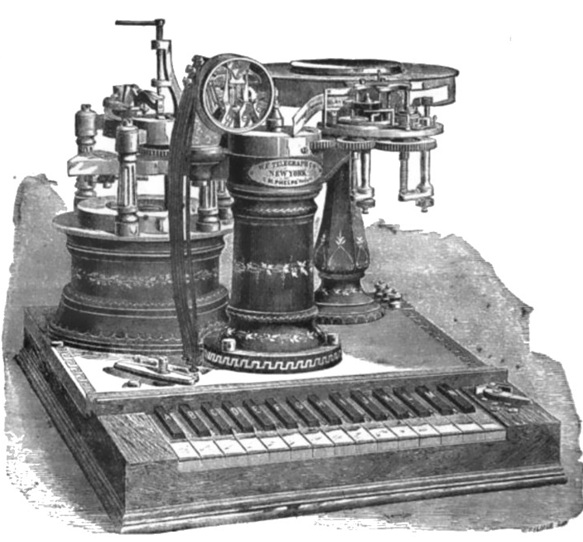

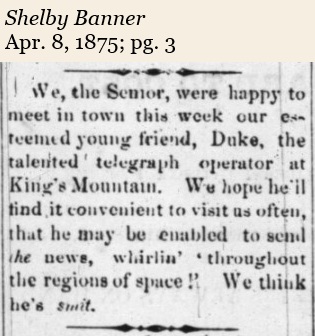

Although the telegraph came into use in the 1840s, there is no mention of its use in Cleveland County until 1875.

The reference to the “Semor” in the article is probably a reference to the word “semaphore,” which has its origin in Greek for a signaling apparatus.

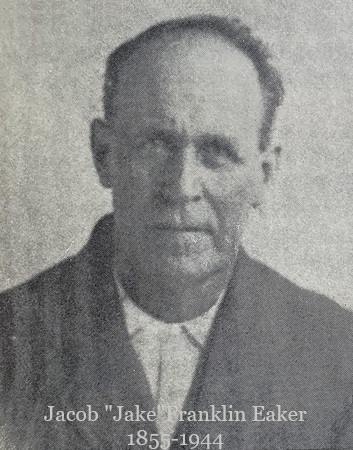

According to Our Heritage, the first use of telephones in the county occurred in the late 1880s. Polkville historian, Lillian Eaker Newton, wrote that her father Jake Eaker and her brother, Edgar Marvin Eaker built and operated a telephone exchange until about 1910.

They had about 200 telephone subscribers paying $1 per year. Eaker’s service area included Delight, Crow’s, Henry, Mountain View, and Toluca. He also ran a line to Shelby, but had to sell some of his land to do it.

About 1890, Henry F. Schenck and son, John Schenck built a private telephone line running from their office at the Cleveland Mills in Lawndale with offices in Double Shoals and five in Shelby. James Digh started an exchange in Lawndale in 1907.

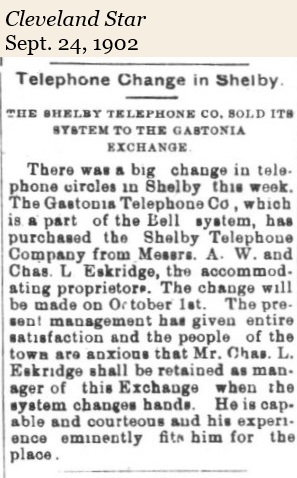

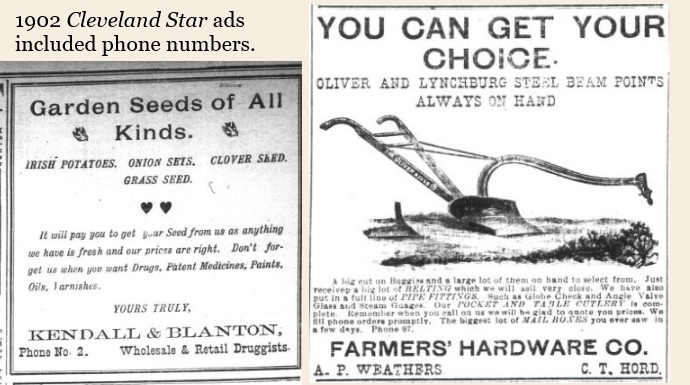

In 1895, William Shuford established a telephone exchange in Shelby. He sold it to Alfred W. and son, Charles L. Eskridge.

In 1902, they sold their exchange to Gastonia’s Piedmont Telephone Company which was part of the Bell system.

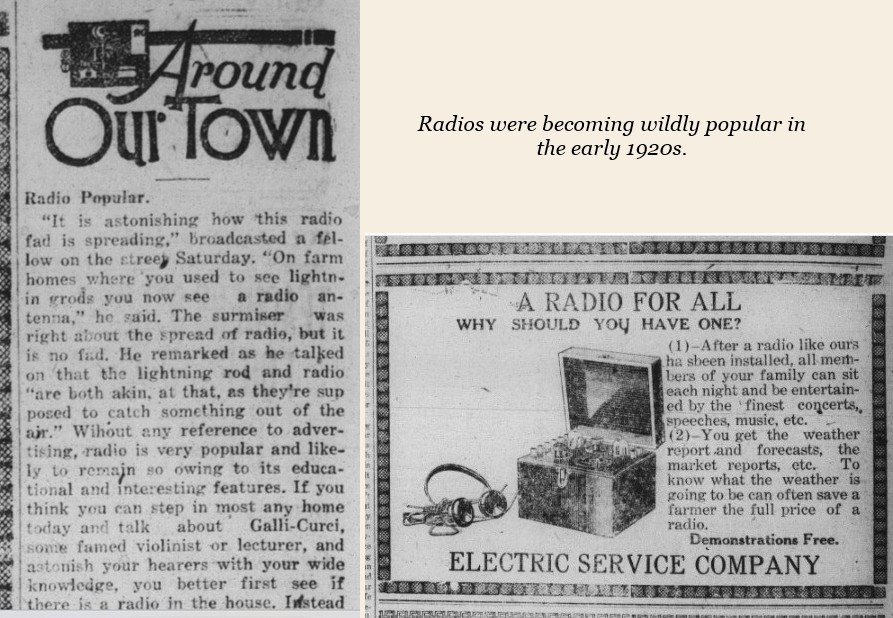

WOHS. The first radio station in Cleveland County started in 1946 as WOHS, 730 AM. Robert Wallace was the manager and soon turned over the programming to Hugh Dover. Dover had a popular morning show called “Carolina in the Morning.” One segment of his show was wishing happy birthday to those having a birthday, and so became known as the “Happy Birthday Man.”

Both Don Gibson and Earl Scruggs went on WOHS. Dover and Scruggs had been childhood friends, growing up in the Flint Hill community. Dover’s show ran for 38 years. Below is an audio of Hugh Dover interviewing Earl Scruggs.

In the 1960s, high schooler Doug Limerick worked at night at WOHS playing Top 40 hits. Limerick went on to become a news correspondent for ABC Radio Network. Limerick won two Edward R. Murrow awards–one for his coverage of the terror attacks on 9/11.

In 1992, Calvin Hastings bought WOHS. It would become one of four radio stations owned by Hastings known locally as the Piedmont Superstations. It aired numerous sports events and changed its format from country music to oldies.

In 2007, WOHS made national and international news when DJ Tim Biggerstaff began to have a seizure while on air. He asked for help on the air and a listener called 9-1-1. He ended up being interviewed by BBC London, Today and People Magazine.

By April 2009, WOHS went silent. Its dormant license was purchased and moved to Cramerton, NC; its call letters were changed to WZGV. In 2010, another Shelby radio station, WADA, took the WOHS call letters.

WKMT. When Don Gibson hosted “Sons of the Soil” on WOHS in the early 1950s, he told Jonas Bridges, an announcer on the show, that he would write a song that would make him rich. Bridges didn’t believe him, but he ended up playing “Oh Lonesome Me” on WKMT in 1957.

In 1953, R. H. Whitesides built WKMT, 1220 AM radio in Kings Mountain. It was signed on by Jonas Bridges who would later become its owner. The station changed its call letters to WDYT in 2006.

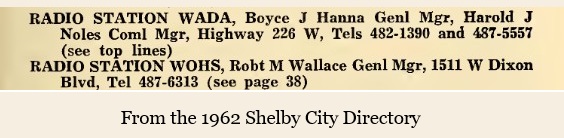

WADA. In 1958, Boyce Hanna and Harold Knowles began the operation of WADA radio, 1390 AM. Later Hanna became the sole owner.

In 1986, the president and general manager of the station, Debbie Clary, changed the format from country music to talk radio. She was among the first in the area to start airing “The Rush Limbaugh Show.”

In 2010, WADA took the WOHS call letters.

WBTV in Charlotte, NC, officially signed on the air on July 15, 1949, becoming the first television station in the Carolinas. Announcer Jim Patterson introduced the station.

For the next couple decades, Cleveland County Baby Boomers would watch TV from only three or four TV stations: WBTV, Ch. 3, WSPA, Ch. 7, WSOC, Ch. 9, and WLOS, Ch. 13.

Cable TV became available in Cleveland County in the 1970s operating under the management of Floyd Williams.

In the mid to late-1970s Cleveland County experienced the CB radio Craze. Following the 1973 oil embargo and the implementation of a 55 mph national speed limit, truckers used CBs to coordinate protests, locate fuel, and warn each other about police. The phenomenon spread from truckers to the general public, with over 20 million radios in use by 1977. Users adopted “handles” (nicknames). Famous terms included “10-4” (message received), “breaker 1-9” (initiating a call), and “put the pedal to the metal” (speeding).

In 1982, C19 began operating at Cleveland Technical Institute, now Cleveland Community College.

Shelby Cable TV was acquired by Time-Warner Cable, which later became Spectrum.

Then came The Internet and cell phones and things would never be quite the same.