Prior to the early 1900s, informal games like stickball, tag, and hopscotch were common pastimes for children. Pick-up games were quite common as well–and very valuable according to Joseph Foster, former Professor Emeritus of Anthropology and Linguistics at the University of Cincinnati . . .

“When I was growing up on the edge of a small “city” in Arkansas, we regularly had “pick-up” football and baseball games in vacant lots or large front or side yards among kids in the neighborhood. You chose up sides from among whoever showed up to play. They were semi-organized in the sense that they were organized and the ground rules established and modified as needed by consensus among the kids themselves– there was rarely any adult within 500 yards of the place. And there were no “officials,” no referees, umpires, field judges, back judges, nor head linesmen. So we learned negotiation and how to deal with ambiguities when nobody could tell for sure whether that ball or some player was out of bounds or not. You won some and you lost some and learned to give and take if you wanted the games to continue and other kids to continue to want you to play with them.”

Often, it didn’t take much to entertain children in the old days. Searching for four-leaf clovers, cracking chestnuts, or popping the buds off a plaintain weed was just enough.

By the 1920s schools and communities began to introduce structured sports programs, primarily focused on physical fitness. The development of Little League Baseball in 1939 marked a turning point, setting the stage for the organized participation of millions of kids around the country.

By the 1950s, there was a tremendous expansion of youth sports due to the Baby Boom. In the 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement led to desegregation of teams affording new opportunities for African American youth. Interscholastic sports, particularly football, baseball, and basketball, gained popularity. The development of high school sports associations and governing bodies formalized rules and schedules, leading to a more organized and competitive landscape.

In 1972, the passage of Title IX prohibited gender-based discrimination in educational programs, including sports. This legislation opened doors for female athletes and led to the rapid growth of girls’ sports.

Minor League Baseball

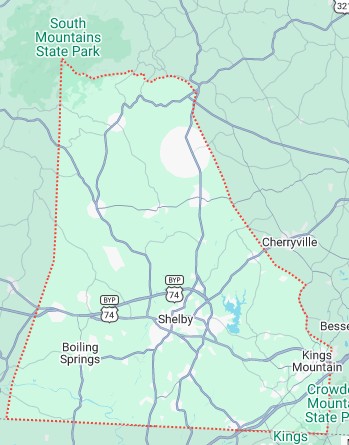

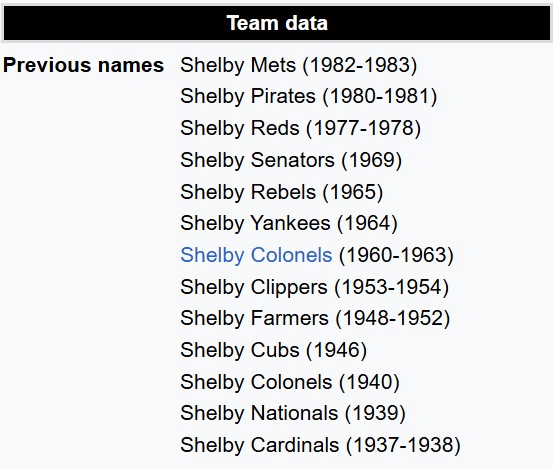

Shelby has a history of hosting minor league baseball teams. Minor league baseball was first hosted in Shelby in 1936, when the Shelby “Cee-Cees” played the season as members of the independent Carolina League. The league played the 1936 season as an eight-team league.

In 1937, the Shelby “Cardinals” became charter members of the reformed the eight–team Class D level North Carolina State League. In 1939, the Shelby “Nationals” resumed minor league play after the Shelby franchise had relocated during the previous season. The Nationals resumed play as a minor league affiliate of the Washington Senators, while joining a newly formed league. The team was renamed as the Shelby “Colonels” and continued play as the 1940 Tar Heel League remained with the original six teams, before the Washington Senators affiliated Shelby team folded during the season.

In 1946, Shelby returned to minor league play following World War II as members of the six-team Class B level Tri-State League. The Shelby “Cubs” played the season as a minor league affiliate of the Chicago Cubs.

Shelby, North Carolina next hosted league baseball play in 1948, when the Shelby “Farmers” became charter members of the newly formed eight–team Class D level Western Carolina League.

After the 1952 season, the Western Carolina League combined with the North Carolina State League to form the ten–team Class D level Tar Heel League, which played in the 1953 and 1954 seasons before folding. The renamed Shelby “Clippers” partnered with the Forest City Owls, Hickory Rebels (Chicago Cubs affiliate), High Point-Thomasville Hi-Toms, Lexington Indians, Lincolnton Cardinals, Marion Marauders, Mooresville Moors, Salisbury Rocots (Boston Red Sox affiliate) and Statesville Blues teams in beginning Tar Heel League play on April 24, 1953.

The Shelby franchise continued play in the 1953, and the Clippers finished the 1953 season in third place in the ten–team Tar Heel League. Several other teams came and went over the years up until at least 1983. All of these teams played at the old Veterans Field on the north side of the 300 block of Sumter Street in Shelby. Read more. . .

Youth League Sports Teams

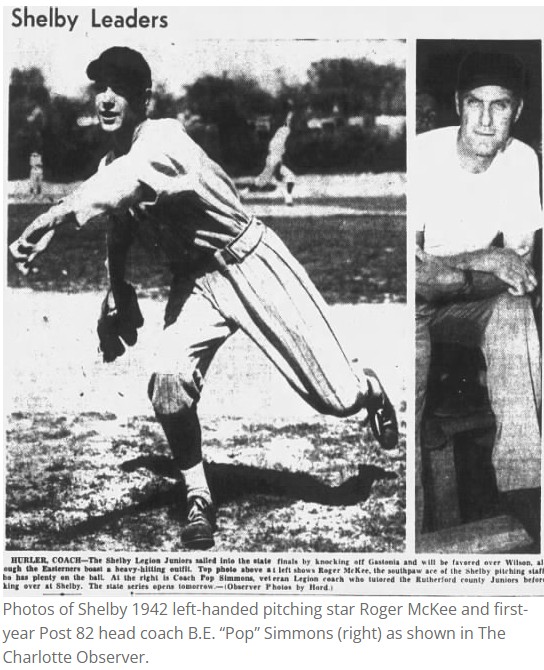

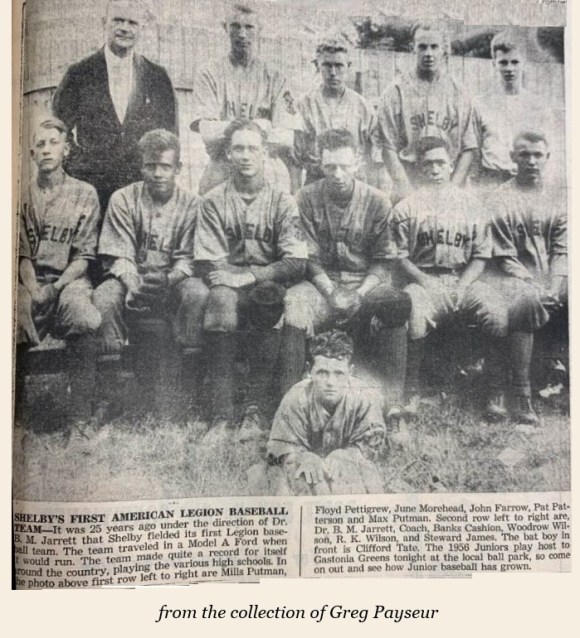

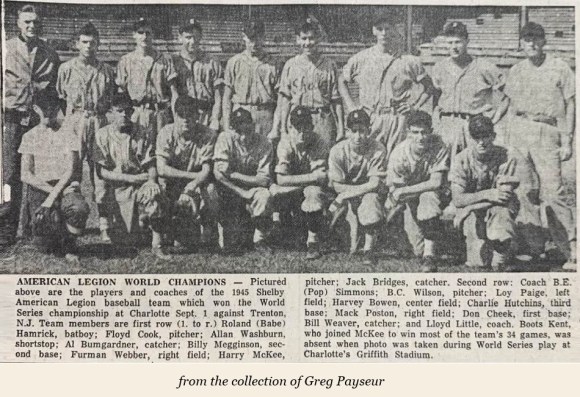

A little history of Shelby’s American Legion Baseball program.

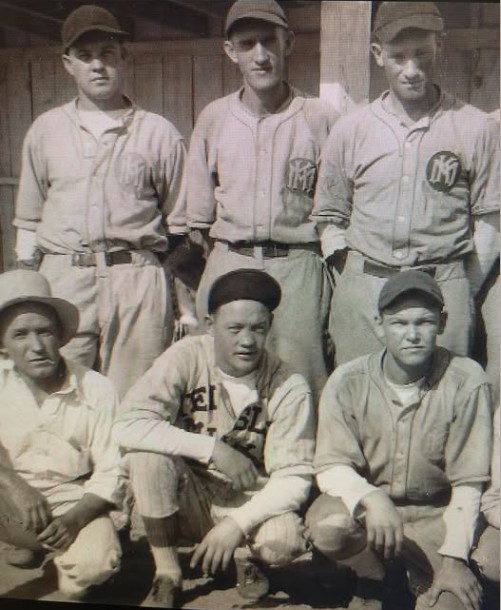

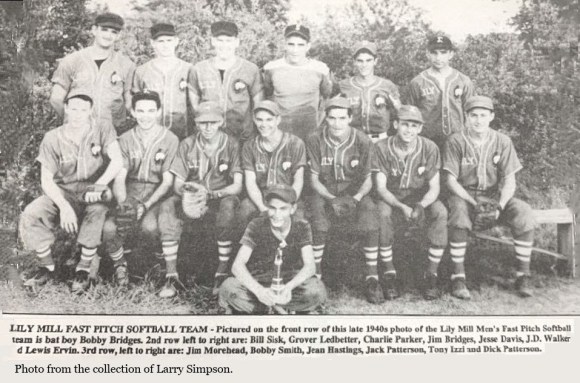

Industrial League Sports Teams

In the past, Shelby was home to a bowling alley where leagues could form and compete. Buddy Carter of Shelby wrote a brief history of bowling in Shelby.

Motorsports

Cleveland County has a rich history in motorsports, particularly with the Cleveland County Fairgrounds Speedway (also known as Shelby Motor Speedway). The speedway hosted NASCAR Cup Series races from 1956 to 1965; other forms of racing continued there until 1976.

Drag racing was once very popular in Cleveland County. The Shelby Drag Strip operated from 1967 to the 1970s, introducing many to the sport of drag racing. Roger Ivester has compiled a brief history of drag racing in Shelby. It is here.

Shadyside Drag Strip also operated in Cleveland County.

More information is available at the Combs Family Museum.

Three Cleveland County drivers have been inducted into halls of fame for their driving careers. Gene “Stick” Elliott was inducted into the National Dirt Late Model Hall of Fame in 2009. Tommy Mauney was inducted into the North Carolina Motorsports Hall of Fame in 2012. Billy Standridge was inducted into the Cleveland County Sports Hall of Fame for his success in NASCAR in 2019.

Cleveland County Sports Hall of Fame

1965: R.W. “Casey” Morris

1966: B.E. “Pop” Simmons

1967: Lloyd Little

1968: Buck Archer

1969: Gerald Allen

1970: Bobby Bell

1971: Hoyt Bailey

1972: Eddie Holbrook

1973: Tom Wright Sr.

1974: Mel Phillips

1975: David Thompson

1976: John Winston

1977: Roger McKee

1978: Pete Webb

1979: George “Fluffy” Watts

1980: Robert Reynolds

1981: Katherine Reynolds

1982: Virgil Weathers

1983: Earl Parker

1984: Malcolm Brown, Norman Harris

1985: Shelby Post 82 1945 American Legion world champions

1986: Gene Kirkpatrick

1987: Bud Hardin

1988: Jim Taylor, Tim Wilkison

1989: Ed Peeler

1990: Bill Proctor

1991: Jim Horn

1992: Dr. Lonnie Proctor

1993: Blaine Baxter, W.E. Halyburton, Hal Dedmon

1994: John Henry Moss

1995: Billy Champion, Manley Runyans

1996: Art Moss, Bill Lynn

1997: Jake Early, Don Patrick

1998: Leonard Morrison, Henry Jones

1999: Steve Curtis, George Litton

2000: Jim Washburn, Alvin Gentry

2001: Ron Greene, Jerry Bryson

2002: Bob Ingle, Charlie Harbison

2003: Dick LeGrand, George Corn, Marjorie Crisp

2004: Sid Bryson, Jim Corn, Lester Dixon

2005: Wade Vaughn, Gene Latham, Tee Burton

2006: Suzanne Grayson, Charlotte Smith, Millie Keeter-Holbrook

2007: John Taylor, Roy Kirby, Chris Norman

2008: Stan Sherman, Tommy London, Kent Bridges

2009: George Adams, Kenneth Howell Jr,, Bob Litton

2010: Mike Grayson, Alan Ford, Tony Wray

2011: Jack Patterson, Woody Fish, Scottie Montgomery, Ralph Dixon Sr

2012: David Steeves, Frank Love Jr., Bryan Jones

2013: Chad Holbrook, Bobby Lane, Tom Wright Jr.

2014: Burney Drake, Richard Gold, Steve Sherman

2015: Joe Craver, Charlie Holtzclaw, Blandine Tate

2016: Coleman Hunt, Jeff Jones, Steve Moffitt, Cliff Wilson

2017: Kevin Mack, Tony Scott, Phil Wallace

2018: Dremiel Byers, Andy Foster, Dan Greer, Aubrey Hollifield, Marcus Mauney

2019: Derrick Chambers, Jackie Houston Falls, Billy Standridge, Mike Stewart

2020-21: canceled (coronavirus)

2022: William Grant “Hoss” Duncan, Shamar Finney, Bob Jones, Charlie Noggle, Jerry Ratchford, Lance Ware 2023: Rodney Robinson, Herbert Harbison, Mike Haggard, Glenn Davenport, Susan Briggs, Matt Arey 2024: Dunsey Harper, Rachel White, Robert “Quickie” Williams, Shonda Cole Wallace 2025: Dianna Sweezy Bridges, Otis Cole, Fredia Lawrence-King, Michael “Fatback” McSwain

YMCA

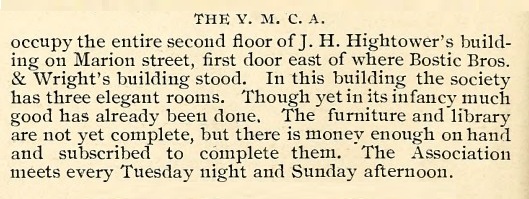

Cleveland County is home to three YMCA facilities. The YMCA in Shelby goes back to 1889, as evidenced by its mention in the brochure, “A Brief Sketch of Shelby.”

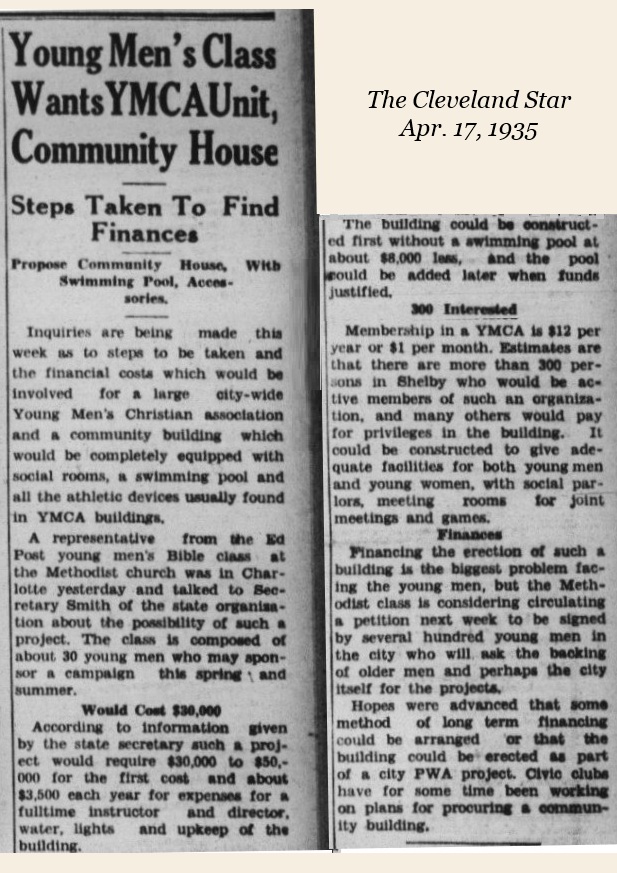

Another mention of the Y was in 1935 when the young men’s class at Central Methodist Church proposed the establishment of a YMCA, although the outcome of that proposal is unclear.

According to Cameron Corder, the current iteration of Shelby’s YMCA began in 1992 as some friends getting together in the basement of Robin Hendrick’s house. From 1994 to 2000, the YMCA was located at 404 East Marion Street in Shelby. In 1997 the Dover Foundation provided the lead funding for the construction of a new facility. This facility was built at 411 Cherryville Road in Shelby and opened in 2000.

The Kings Mountain YMCA opened in 2000, followed by the Ruby C. Hunt Family YMCA in Boiling Springs in 2008.

Parks and Recreation Centers

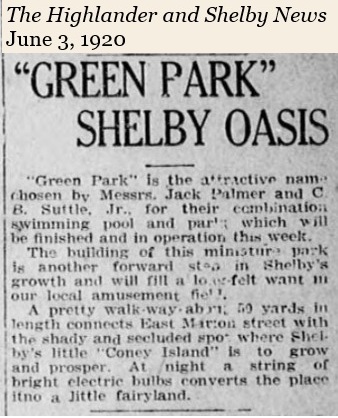

One of the earliest known parks was the Green Park in Shelby. It was located between East Marion and Suttle Streets (possibly on the northwest side of present-day Brookhill.) It had a swimming pool freely open to the public although the park itself was privately owned by Jack Palmer and Charles B. Suttle.

The need for a municipal park was first recognized in the county in 1935, as evidenced by the Cleveland Star clipping below.

In May 1947, the Shelby City Park project began with surveying, planning, and purchasing of property to build a Community Center as a memorial to those who served in World War II. The Parks and Recreation Department was supported exclusively by revenues from 420 parking meters in the City of Shelby.

The city park included an Olympic-size swimming pool, a 12-foot-deep diving well, baseball fields, and a nine-hole golf course. Inside the center was a gymnasium and a small bowling alley. There were also attractions for children such as a kiddy pool, playground, carrousel, and train.

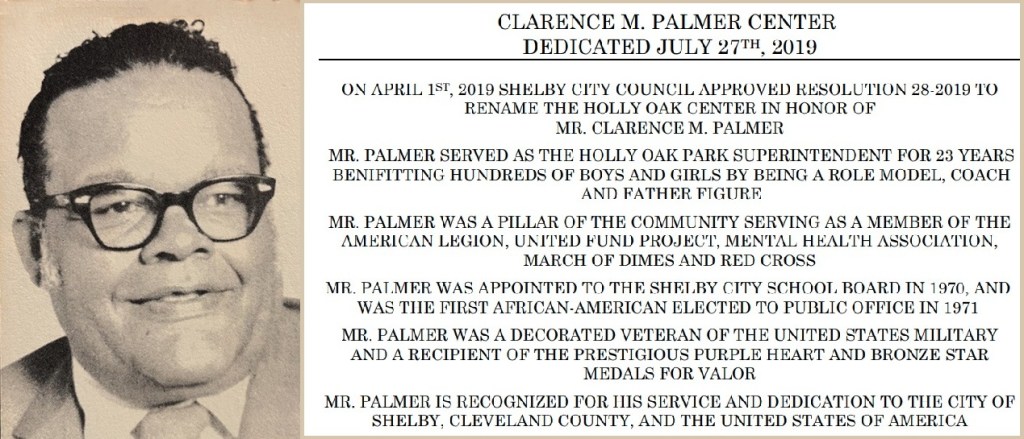

In 1949 another park was established in Shelby. Serving the African American community in the era of segregation, the park was named Holly Oak Park. In 2019, the park was renamed to honor the park’s first administrator, Clarence Palmer. Forrest Toms spoke at the rededication ceremony: “Holly Oak Park was at the center of Black athletics and Black life in Cleveland County and even drew in people from surrounding cities including Charlotte.” Read more. . .

In 1990, Cleveland County’s Master Park and Recreation Plan recommended the county provide passive recreation facilities

and the towns should concentrate on active recreation facilities.

In Kings Mountain, the Jake Early Sports Complex has been in operation since 2001. The complex includes three softball fields, a fourth one that doubles as a soccer field, the Deal Park Walking Trail, and the Rick Murphey Children’s Park.

Crowders Mountain State Park is located just southeast of the city of Kings Mountain. While most of the park is located in neighboring Gaston County, the portion that includes the Boulder Access and about 4.7 miles of the Ridgeline Trail is in Cleveland County. (Note: There is also the Kings Mountain State Park and the Kings Mountain National Military Park where the Revolutionary War battle took place. Both of these parks are in South Carolina.)

In 1970, threatened with the prospect of the land being sold to a strip-mining company for its kyanite, concerned citizens set about to insure the area was preserved. In 1971, members of the Gaston College Ecology Club organized a protest march to save Crowders. These grassroots efforts worked and by the summer of 1974, Crowders Mountain State Park opened to the public.

The Broad River Greenway was established in 1994. This natural preserve consists of 1436 acres lying on either side of the Broad River. The preserve is very popular among hikers, paddlers, and campers.

In 1997, Steve Padgett, a local contractor who specializes in restoring log structures, was hired to move a log cabin to the Greenway. This cabin was originally constructed along the banks of Beason Creek, southwest of the city of Kings Mountain. Read more.

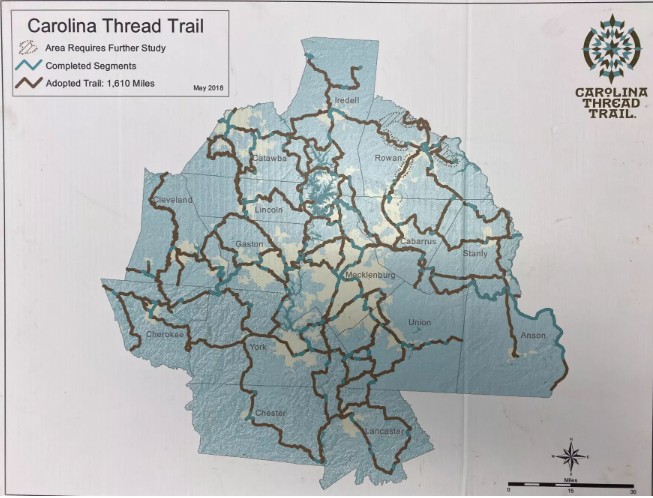

In 2007, the Carolina Thread Trail project was officially launched. It was founded as a project by the Catawba Lands Conservancy and aims to connect people to nature through a network of trails. Cleveland County is one of 15 counties making up the network of trails. Read more.

The Stagecoach Greenway in Lawndale originated with Cleveland County Water in 2017. Upon completion it will consist of 60 acres of land, a five mile trail, and four parks. Read more.

South Mountains State Park is one of the largest in the NC state parks system. Development of some land within the current park boundaries, including construction of certain trails that are still in use, actually began in the 1930s under the Civilian Conservation Corps. It was established as a state park in 1974 and opened to the public in 1975. A portion of park lies in the NW corner of Cleveland County, however the access points into it are all on the Burke County side.