African American history in Cleveland County, like all counties of the Southern states, is deeply intertwined with the legacy of slavery and the subsequent struggles for freedom and equality. Prior to emancipation, information about Cleveland County African Americans is very limited. But according to the Cleveland County Historical Society’s 1991 sesquicentennial “Heritage Day” pamphlet, as many as 15 African American men fought at the Battle of King’s Mountain on the Patriot side.

The 1860 census records the total number of enslaved people living in North Carolina as 331,059. The number in Cleveland County accounted for less than 1% of that total–equating to 2,131 enslaved people. Of these 1,973 were black and 158 were “mulatto.” There were also free people of color living in Cleveland County–four black and 105 mulatto. Prior to emancipation, about 3% of Cleveland County’s white land owners held slaves.1

According to Mamie Jones, a Cleveland County historian, four black men from the county became members of the Freedmen’s Association headquartered at Fisk University in 1866. They were John Bridges, Elick Jennings, Henry Johnson, and Dan Wilkins.

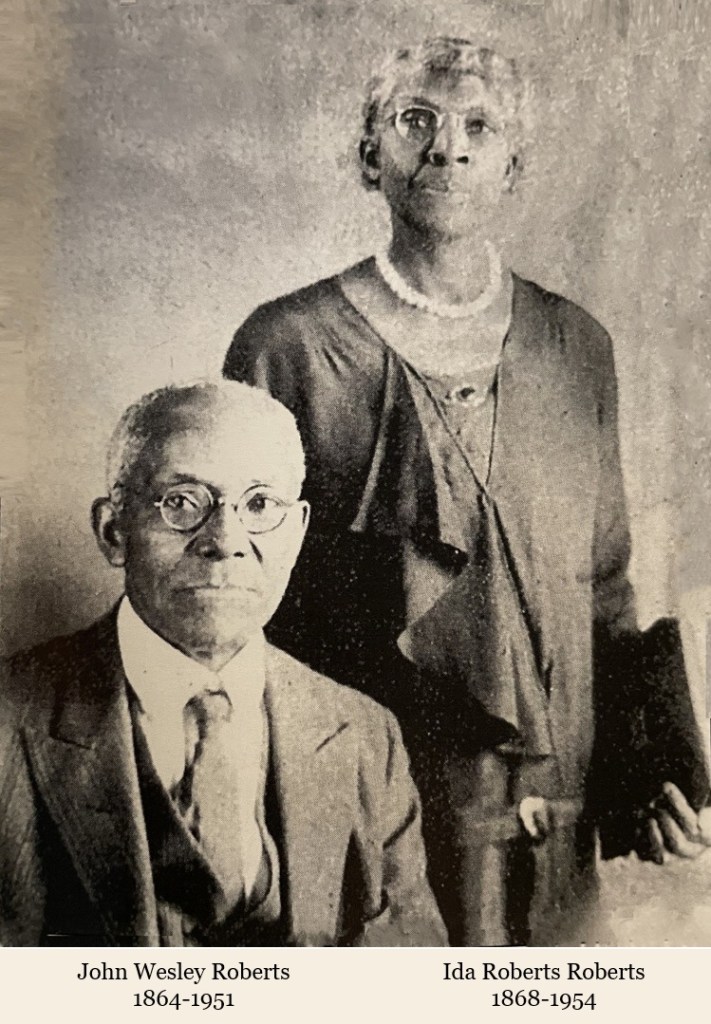

Born one year after the Emancipation Proclamation, John Wesley Roberts grew up to become a well respected leader in Cleveland County. Mr. Roberts was the first college educated African American in the county after earning a Bachelor of Science degree. He furthered his education and earned a Doctoral degree in Divinity. Rev. Roberts became an elder in the CME Zion Church and founded Roberts Tabernacle CME Church in Shelby, NC. He was also the first principal of Cleveland High School. His wife Ida was also college educated and became a longtime teacher. In 1915, she became the first woman ordained.

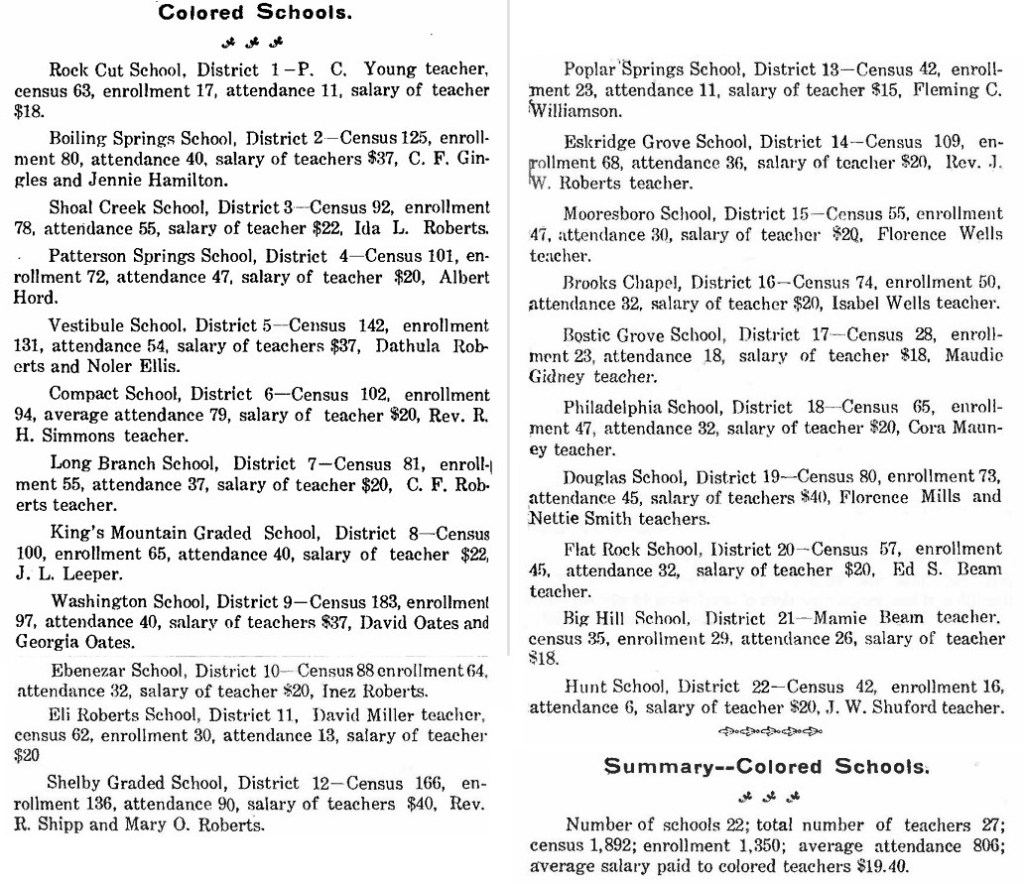

prepared by Superintendent Bayard T. Falls.

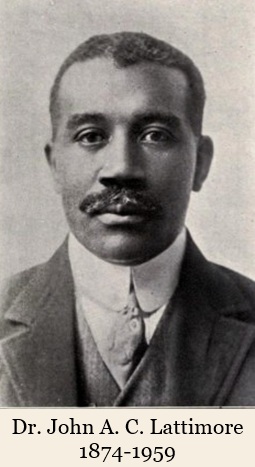

Dr. John Aaron Cicero Lattimore, born in Lawndale, was a physician and civic leader. After moving to Louisville, KY, he became an organizer of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Louisville Urban League. For a time he headed the National Organization of Negro Physicians.

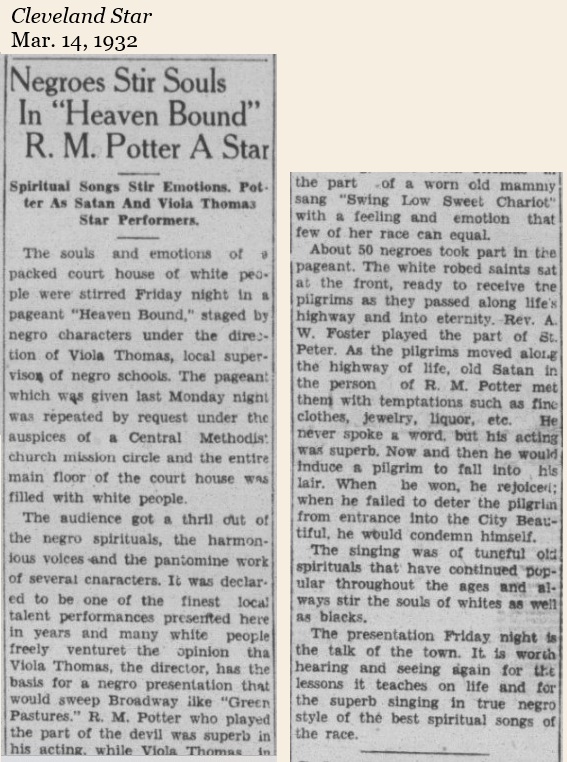

Another leader in the African American educational community included the Rev. Adolphus Warren Foster who was principal of Cleveland Training School for 11 years. He was at Douglas High School for 21 years.

A. W. Foster also performed in the Shelby presentation of the play Heaven Bound, an African American folk drama. Written by Lula B. Jones and Nellie L. Davis of Atlanta, the play portrayed the struggles and pitfalls of a group of pilgrims striving to reach the gates of heaven. The Shelby production was directed by Viola Thomas, supervisor of Black schools in Cleveland County at the time. The play was well received and widely acclaimed.

The Ayfield Hoskins family has been cited in the educational field as well. Ayfield and his wife, the former Bernice Shivers, raised seven children–all of whom received a college education. One son, James D. Hoskins, taught school in Lawndale for three years before joining the Shelby School System. He served that system for 43 years, 34 of them as principal of Cleveland School, a high school until 1967. Two daughters, Marilyn H. Cabaniss and Virginia H. Sasportas taught for many years taught in the county.

On February 1, 1960 four Black North Carolina A & T freshmen sat down at the lunch counter inside the F. W. Woolworth store in Greensboro, NC. They had purchased toothpaste at the store with no problems, but were then refused service at the store’s lunch counter when they each asked for a cup of coffee and a donut. They were refused service and asked to leave; they did not budge. Their “sit-in” sparked a nation-wide movement over the next six months.

On February 18, 1960, a group of Black high school students held a sit-in at the Smith’s Drug Store and bus station lunch counters in Shelby. Their courageous stance helped further the civil rights movement locally.

Some time after the sit-ins, Waddell Chapel AME Zion Church pastor, Reverend Tecumseh Xavier Graham, became the first African American to serve on a city wide board–the parks and recreation commission. Born in Washington, DC, Graham served many communities in his capacity as a Methodist minister. He died in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1998.

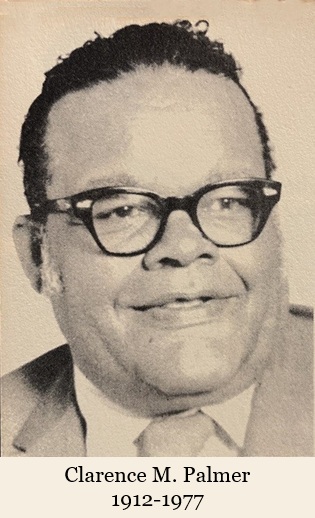

The first elected African American official in the county was Clarence Palmer, director of Holly Oak Park. Mr. Palmer was elected to serve on the Shelby Board of Education in 1971, having already served an unexpired term in 1970.

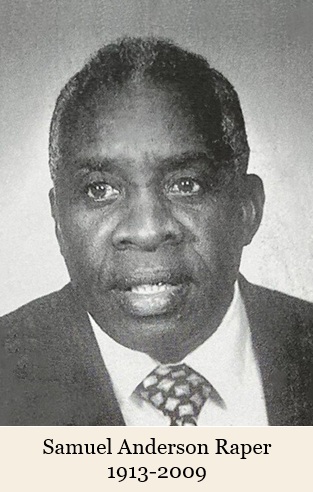

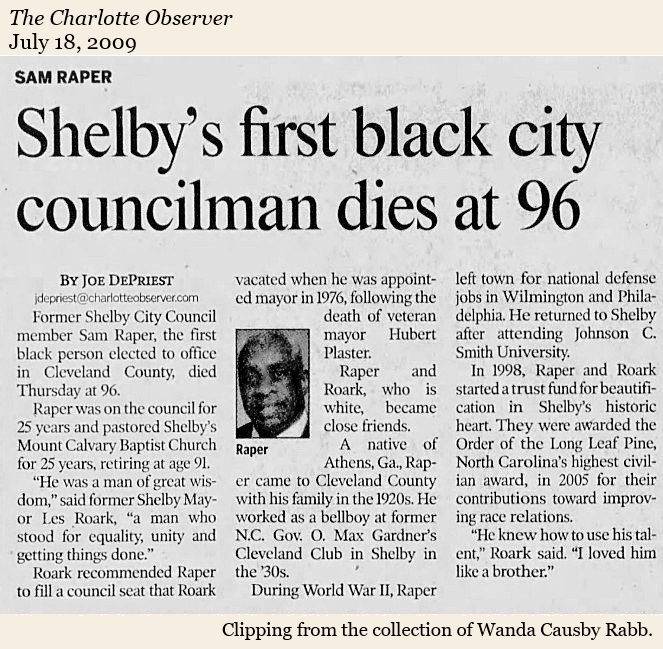

In 1976, the Reverend Sam Raper was elected to serve on the Shelby Board of Alderman. According to family friend, Wayne Merritt, as a young man Mr. Raper had a job breaking horses. He literally lived by the adage, “If you fall off a horse, get right back on!”

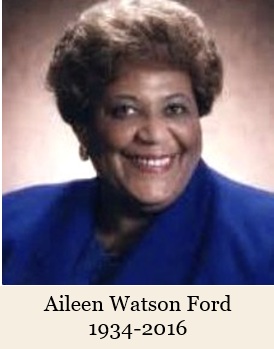

Aileen Watson Ford was notably the first female to hold a governmental position in Cleveland County when she was elected to serve on the Shelby City Council in 1983. She was also the second African American to serve on the council, serving for 12 years, from 1983 to 1995.

Among other African American leaders have been David Banks, J. W. Borders, Mattie Peeler, and L. J. McDougal.

Johnny and Shirley Searight, although not born in Cleveland County, came here in the early 1970s to attend Gardner-Webb College; Johnny was a basketball standout there. Since then they have made Boiling Springs their home and have given back to their alma mater with the establishment of the Searight Professional and Continuing Education (PACE) program at Gardner-Webb University.

Several African American sports standouts were born in Cleveland County. Read about Bobby Bell, Floyd Patterson, Mel Phillips, and David Thompson and many others on the “Sports Pros” tab.

Early Churches & Schools

The following are some links to African American history specific to Cleveland County:

African American History in Cleveland County: A Scrapbook. Includes news clippings, correspondence, photographs, funeral programs, cards, and more, mostly pertaining to the African American community in Cleveland County, North Carolina.

African American History and Education in Cleveland County. Compiled by Ezra Bridges, this scrapbook includes news clippings, correspondence, postcards, photographs, funeral programs, and more, mostly pertaining to the African American community or education in Cleveland County, North Carolina from 1940-1977.

The Cleveland County African American Heritage Trail. Created by Zachary Dressel, this site provides a virtual tour of important sites of African American Heritage in Cleveland County, NC.

The Cleveland County Sesquicentennial Booklet prepared in 1991 contains an article about some of the county’s African American leaders.

Cemeteries

The following are some of the known cemeteries where descendants of the county’s former slaves were buried:

Brook’s Chapel Methodist Church, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census.

Brook’s Chapel Methodist Church Cemetery, updated 1998 by W. D. Floyd. Map.

Ellis Chapel Baptist Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census.

Ellis Chapel Baptist Cemetery, updated 2001 by W. D. Floyd. Map.

Eskridge Grove Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Green Bethel Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census

Green Bethel Baptist Church Cemetery, updated 1998 by W. D. Floyd. Map.

Ivey Hill Methodist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census

Long Branch Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Philadelphia Methodist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census

Philadelphia Methodist Church Cemetery, updated 2001 by W. D. Floyd. Map.

Shiloh AME Zion Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Shoal Creek Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census

Shoal Creek Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

St. Paul’s Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Vestibule Methodist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Vestibule Baptist Church Cemetery, updated 2001 by W. D. Floyd.

Washington Baptist Church Cemetery, 1939 WPA Cemetery Census. Map.

Webb Memorial Lawns, Eaves Rd. Shelby, NC 28152. Map.

Young’s Chapel AME Zion Church, updated 2001 by W. D. Floyd. Map.

In 2021, Zachary Dressel and Joe DePriest were visiting Sunset Cemetery when DePriest pointed out to Dressel a large area on the west side of the cemetery that was devoid of headstones. DePriest had heard that was “the old cemetery” where enslaved people had been buried. Dressel began researching this area and learned the old Shiloh church and a school were located on this land as well.

After presenting this information to the Shelby City Council, a commission was organized to investigate the “Forgotten Colored Cemetery.” That investigation is ongoing.

https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1860/population/1860a-27.pdf